“If you want to be happier, wholeheartedly welcome your grief.” -Andrea Gibson, American Poet and Activist

Definitions

When someone experiences great loss there are typically three words used to describe the experience: mourn, bereavement, and grief.

The Latin root word for grief, gravis, also gave English the word gravity. Gravis, an adjective, also means ‘heavy, weighty,’ and it formed the basis of the verb gravare ‘weigh upon, oppress.’” (Ayto, 2011)

A root word for mourn, morna, also gave English the word remember. (https://www.etymonline.com/)

Bereavement refers to “the period of grief and mourning after a death”. (medlineplus.gov) The root word for bereavement from the Old English, bereafian, also gave English the words rob and deprive (https://www.etymonline.com/)

So, bereavement means to rob or deprive. Mourn means to remember. And grief refers to feeling the gravity, the heavy weight, the oppression of the situation. These are all part of the grieving process.

Little and Big Griefs

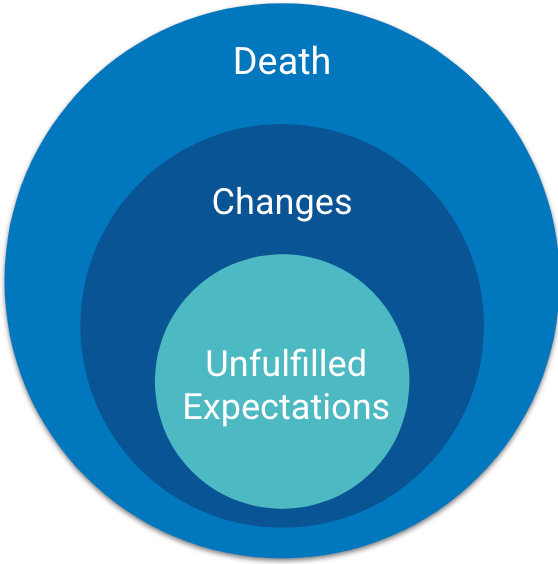

Westberg (2019) talked about two categories of grief – little grief and big grief. Although I’m bothered by the word “little”, these two categories offer hints to a variety of griefs that we experience.

- death

- changes

- unfulfilled Expectations

- the death of a loved one

- family

- friends

- pets

- changes in work

- changes in relationships

- changes in living conditions

- when an expectation goes unfulfilled

“Nothing that grieves us can be called little; by the external laws of proportion a child’s loss of a doll and a king’s loss of a crown are events of the same size.” Mark Twain, ‘Which Was The Dream?’

Deaths, changes, even unfulfilled expectations are all kinds of grief. They are all experiences we can learn from and grow through.

How Grief is Experienced

As a response to loss, grief is universal, but it is not experienced the same way. Cultures and traditions can place expectations on us and give us rituals to help us grieve. Our unique context in our families, at work, our religious experiences, and our ethnographic culture all influence how we experience grief.

Additionally, grief can be experienced physically, mentally, emotionally, and spiritually. This makes each experience of grief unique, even if the same person is experiencing multiple griefs.

Grief can also be experienced through stages, phases, tasks, and/or randomly (Kübler Ross and Kessler (2005); Kessler (2019), Stroebe, Schut, and Stroebe (2007); Davis Konigsberg (2011); Bonanno (2019); Westberg (2019); Parkes (2002)).

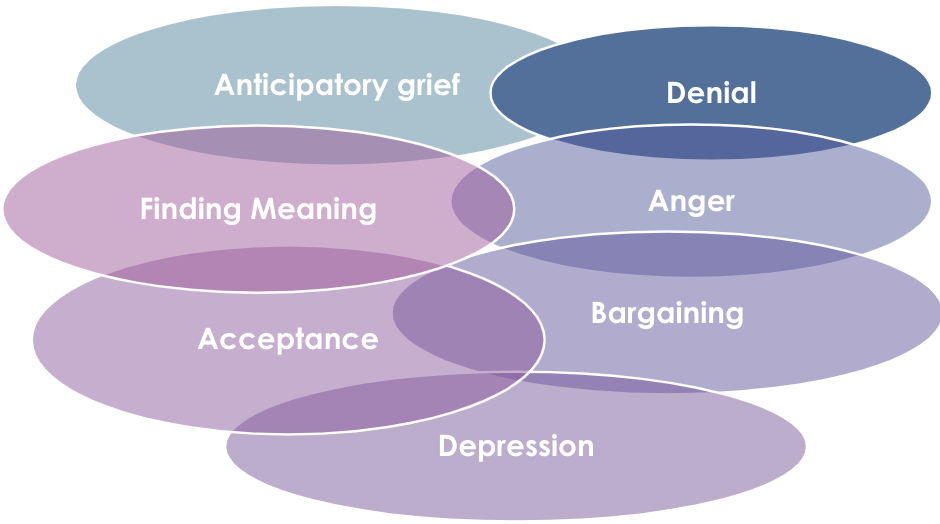

Kübler-Ross and Kessler’s stages of grief is one of the most commonly talked about ways of experiencing grief. These two grief guru’s taught the world about a pre-stage of anticipatory grief, and the traditional five stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. After Kübler-Ross died, Kessler, with the permission of Elizabeth’s family, introduced a new sixth stage, finding meaning.

They are typically taught in the following order

- Anticipatory grief

- Denial

- Anger

- Bargaining

- Depression

- Acceptance

- Finding Meaning

However, that was never Kübler-Ross and Kessler’s intent. The figure below shows the way many people experience the stages – not linearly (in a line), but all mixed up and overlapping.

Deeper Dive into the Stages of Grief

So what do these stages look like?

- Anticipatory Grief happens before a death or change occurs and can be the beginning of the grieving experience.

- Denial is the experience of not being able to fathom the death or change that has occurred.

- Anger does not have to be logical or valid and typically occurs once you feel safe enough to know you will survive (Kubler-Ross and Kessler, 2005, pg 11).

- Bargaining is when our guilt and “if-only’s” lead to finding fault with ourselves and what we think we could have done differently (Kubler-Ross and Kessler, 2005, pg 17).

- Depression in grief (as opposed to clinical depression) is characterized by empty feelings, withdrawal from life, living in the “fog of intense sadness” and questioning whether to go on (Kubler-Ross and Kessler, 2005, pg 20).

- Acceptance occurs when you begin to realize this new reality is a permanent reality and learn to reorganize and reassign roles (Kubler-Ross and Kessler, 2005, pg 25).

- Finding Meaning occurs through “remembering, interpreting, and framing our experiences” (Davis, 2008, p. 8). What does meaning look like? It may take many shapes, such as finding gratitude for the time . . . with the loved one, or finding ways to commemorate and honor loved ones, or realizing the brevity and value of life and making that the spring-board into some kind of major shift or change. (Kessler, 2019, p. 3).

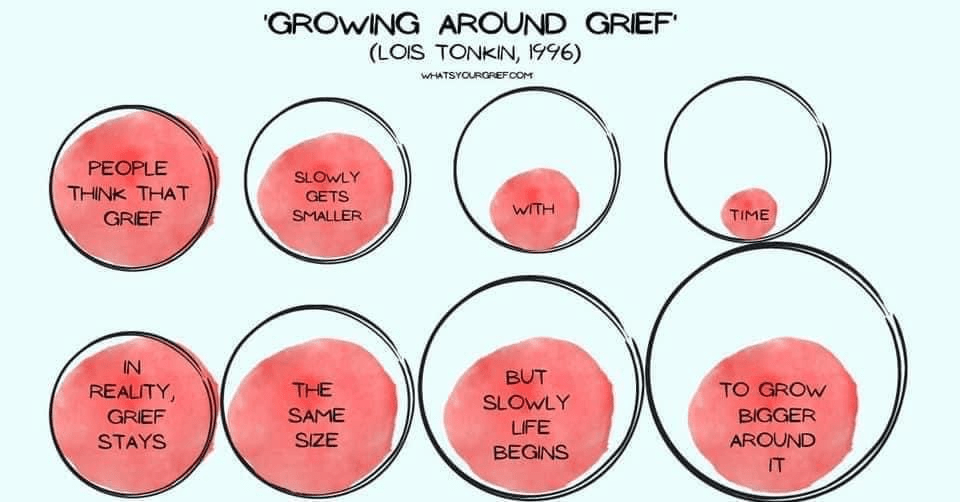

“Grief is never something you get over. You don’t wake up one morning and say, ‘I’ve conquered that: now I’m moving on.’ It’s something that walks beside you every day.” ~Terri Irwin, American-Australian Conservationist

Grief doesn’t just disappear. It rises up again and again as you process through it. That’s where HERO comes in. Strengthening our HERO reservoir can help us grow bigger around our grief.